37. Step1X-Edit

How to build a dataset for text-guided image editing

Introduction

Everybody is (literally) going bananas about image editing these days. From OpenAI’s GPT Image to Google’s new Gemini Flash, closed-source APIs make text-guided edits feel like magic. But how do we even train a model to handle multi-turn editing tasks like the one below? Where do we find the before–and–after image pairs and the instructions that describe the edit?

I found myself asking this question recently, and after coming across a fascinating open-source effort trying to reproduce these closed-source systems, I couldn’t wait to share it with you, as it is not a trivial problem to solve.

The paper we’ll dive into today is Step1X-Edit [1], and while the model architecture itself would be worth a separate deep dive, what really caught my attention and what we’ll focus on in this post is the data pipeline. Enjoy!

Problem setup

We all know what it takes to train a text-guided image generation model like Stable Diffusion: a huge collection of images paired with text descriptions. Technically, both the data and the models are out there for anyone to reproduce.

Thanks to projects like LAION [2], billions of image–text pairs were scraped directly from the web, transforming noisy captions from alt-text and metadata into a massive training set. At this billion-image scale, the data is enough to unlock high-quality text-to-image generation when training a new model from scratch.

We then have simple inpainting and outpainting tasks, where we basically mask out a region, keep the rest as context, and train the model to fill in the missing pixels. Again, no real data problem here, since the image itself becomes the target. This is the same idea behind self-supervised methods like Masked Autoencoders, for example.

However, when it comes to real image editing, where we want to go beyond simple local changes and handle more abstract tasks like switching style, altering poses or colors, or subject replacement, generating data suddenly becomes much harder.

The bad news is that we cannot rely on the same “mask and recovery” trick used to train inpainting. However, the good news is that inpainting itself, assisted by a whole squad of specialized models, is sufficient to handle most of the data generation.

Models

To build a dataset of triples of initial image, text instruction, and edited image, Step1X-Edit combines state-of-the-art models for object detection, segmentation, instruction generation, and image synthesis. Each model excels at one stage of the pipeline, but together they handle the entire process end-to-end. To cover the dozen editing tasks needed for a high-quality dataset, the pipeline uses:

Florence-2. This is a vision-language model (VLM) by Microsoft capable of object detection and image captioning. When provided with an image and a query such as “Locate all objects in the image”, it produces reliable bounding box coordinates and object labels.

Segment Anything 2. This is the second version of the promptable segmenter by Meta, which returns high-quality object masks given an image and an input in the form of points, bounding boxes, or coarse masks.

Qwen2.5-VL and Recognize Anything. In order, a vision–language model from Alibaba, used for multimodal understanding, and an image captioning and recognition model for extracting detailed scene information.

FLUX-Fill and ObjectRemovalAlpha. These are both fine-tuned versions of FLUX, specialized to infill regions in existing images from text prompts and remove objects in specified areas with high fidelity.

ZoeDepth. This is used for depth estimation (honestly, there are better alternatives XD) to provide geometric information that can guide edits.

ControlNet. This is a famous framework for conditioning pretrained generative models on extra inputs such as sketches, edges, segmentation masks, and depth maps. In particular, the authors used ControlNet on top of Stable Diffusion 3.5 to handle edits requiring any of the extra structural information listed before.

RAFT. Used for optical flow estimation on video frames, providing fine-grained motion information and pixel-level displacements over time.

BiRefNet. Handles foreground–background separation, helping the pipeline isolate moving objects in the foreground for motion-related edits.

GPT-4o and Step-1o. These are LLMs for creating and refining instructions used to describe the edits.

Alright, that was a long list! And it’s fine if half of those names sound completely new: that’s just the reality of living in a time when dozens of frontier labs release models every month. What matters here isn’t how each model works under the hood, but what role it plays in building the dataset, which we’ll see now.

The data engine

The authors first taxonomize editing into eleven categories, then build task-specific generation pipelines for each one of them. Starting from a large image pool, they create edited variants using the tools above, followed by a dedicated revision stage.

After rigorous filtering using both multimodal LLMs and human annotators, the process yields about one million high-quality triples. Below are some key categories, along with an explanation of how each triple is produced.

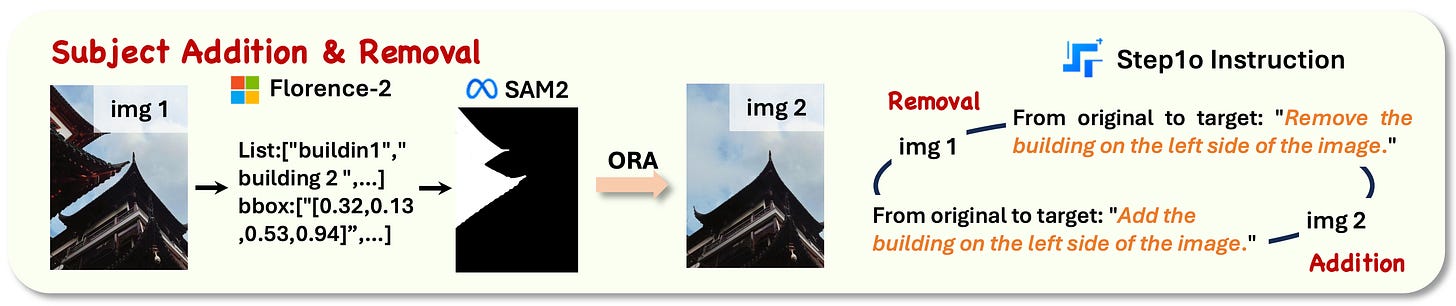

1. Subject addition & removal

First, we detect all objects in the image with Florence-2, returning a set of bounding boxes. We then pick one and pass it as a prompt to SAM 2 for segmentation, returning a detailed mask of that object. Finally, ObjectRemovalAlpha (ORA) performs the inpainting task, substituting the object with the background.

Corresponding editing instructions are generated using a combination of Step-1o model and GPT-4o. And because the operation is reversible, the image pair can be swapped by simply flipping the instruction, for example, changing “add” to “remove”. Cool combination of VLM, segmenter, inpainting model, and LLMs here!

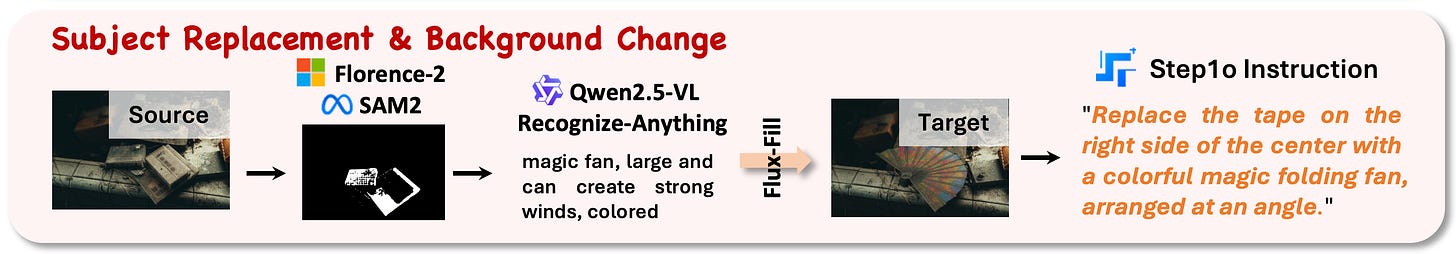

2. Subject replacement & background change

This category shares similar preprocessing steps with subject add/remove, including Florence-2 annotation and SAM 2 segmentation of an object. However, instead of removing the object and substituting it with the background, we follow with Flux-Fill for content-aware inpainting to replace the object with another one.

In particular, Recognize Anything extracts object names to provide richer context, while Qwen2.5-VL interprets the full scene given that information too and crafts the edit request. The final instructions are then polished automatically by Step-1o.

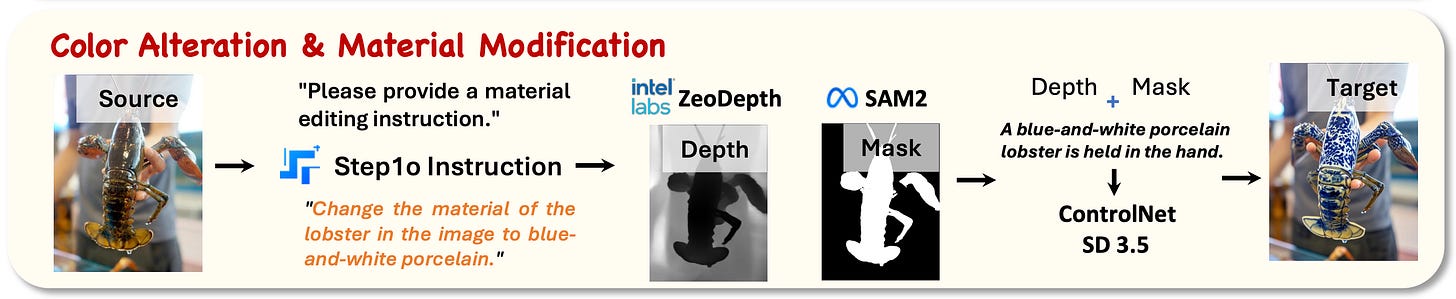

3. Color alteration & material modification

This one is pretty fun! We predict depth with ZoeDepth, and a subject with its mask with SAM 2 via (I guess) Florence-2 input. Then, we alter only the appearance using Stable Diffusion 3.5 ControlNet, passing the mask and depth as extra conditions to ground generation. The instruction describing the attribute change is generated by Step1o, after getting the content of the image.

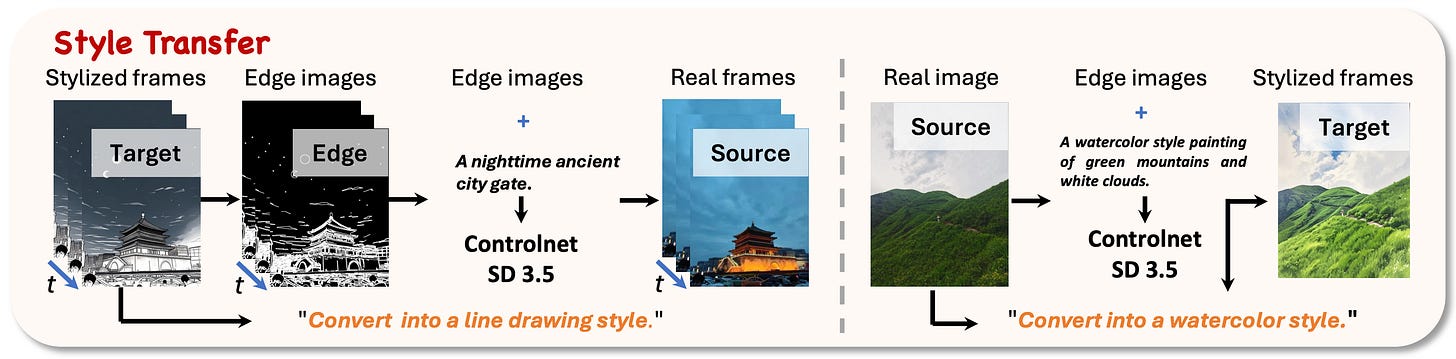

4. Style transfer

Depending on the image style, the pipeline either generates photorealistic images from stylized inputs or, conversely, starts with realistic images and produces stylized outputs. In both cases, edges are the element used to guide generation.

In particular, we extract edges and then use Stable Diffusion 3.5 ControlNet conditioned on edges to keep the scene layout intact. The text prompt for style transfer comes from the same instruction generation stage used across other tasks.

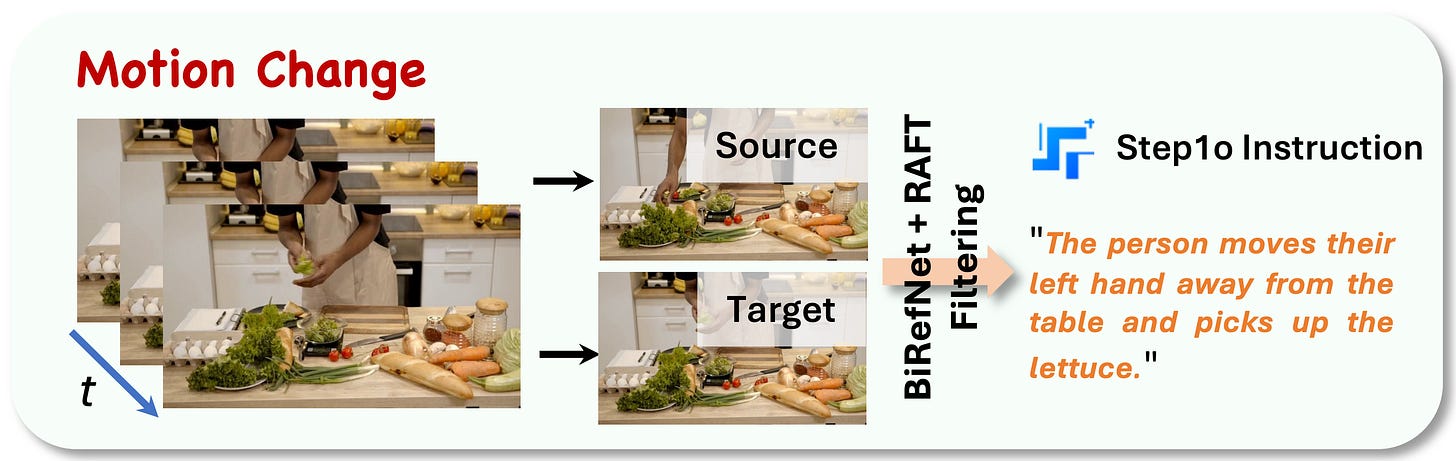

5. Motion change

This task takes advantage of video data to get character consistency and novel views, basically for free. The pipeline samples frames from a video clip, uses BiRefNet to separate foreground from background, and applies RAFT for optical flow estimation in the foreground areas. Once we spot a pair of frames where the foreground actually moves, we write the motion instruction that matches the observed visual delta.

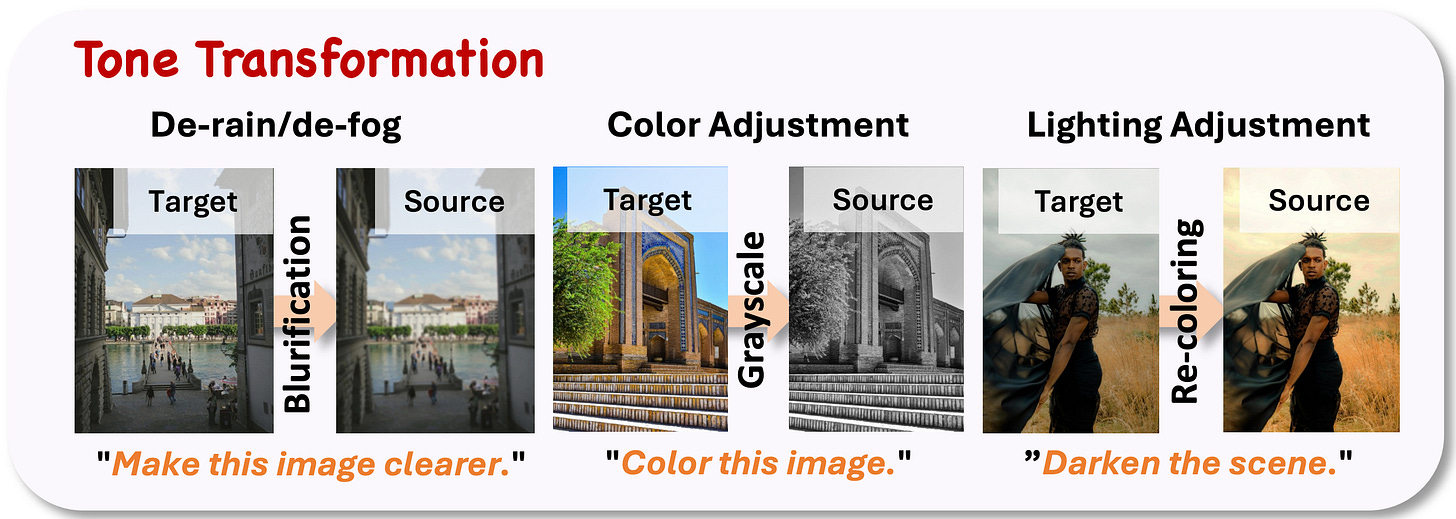

6. Tone transformation

This category focuses on global tonal adjustments, including color and lighting changes, deraining and defogging, and seasonal transformations. These edits are mostly handled by algorithmic tools and automated filters, which apply effects to clean images to simulate realistic environmental changes. A diffusion refinement can also be applied, and again, these are reversible.

While there are other types of editing, they mostly involve manual work from artists, so we are not going to cover those. And even for the automatic pipelines, remember that while models like GPT-4o can score fidelity of the before and after, human reviewers are the ones eventually responsible for filtering out low-quality or unrealistic edits when the model score is questionable.

Given that image editing models are often fine-tuned from image generation ones, we don’t need the same scale of the pretraining data to achieve impressive results. While I couldn’t find any public details on training set sizes from the frontier labs, it can be reasonably assumed that they consist of millions and millions of rigorously curated and validated examples. If anyone reading works on Nano Banana or similar, I would be very curious to get an idea of the order of magnitude of the dataset size :)

In any case, this is some serious engineering pipelining, and it makes me personally satisfied when I revisit the questions about how these triples are made. The most interesting takeaway is that we can use inpainting models as a primitive for image editing, provided that we have other models telling us what, where, and how to edit. However, the more models we pipeline, the more failures we can have, so human verification is often needed in combination with VLM checking.

Conclusions

We took a look at the data pipeline behind Step1X-Edit, exploring how detection, segmentation, depth, instruction generation, and image generation models all work together to produce high-quality data triples to train modern image editing systems.

Technically speaking, nothing prevents this data engine from creating even chains of edits, as long as each edit step is tracked and validated along the way. This is so cool, and as LLMs increasingly focus on synthetic data generation in domains like math and coding, pipelines like this are stepping up to keep pace in the vision domain.

The paper then goes on to train an image editing model using this dataset, essentially reproducing the capabilities of closed-source systems. That part is worth exploring on your own if you’re curious, but I’ll leave a sneak peek here: it involves a multimodal model, a diffusion transformer, and a VAE to map into and out of the latent space. And just with that, see you next time!

References

[1] Step1X-Edit: A Practical Framework for General Image Editing

[2] LAION-5B: An open, large-scale dataset for training next-generation image-text models