44. DINO-Foresight

Predicting the future, but in latent space

Introduction

Predicting what comes next is a really fun problem in computer vision. From robotics to autonomous driving, anticipating the future is essential for long-horizon planning, because a system that outputs control only up to the current frame is already late.

These days, video generation and world models are getting a lot of attention, as they try to generate the next frames and capture how scenes evolve while respecting physical constraints. But to predict the future, do we really need RGB values? Clearly, forecasting images pixel by pixel is computationally intensive and often unnecessary.

With this motivation, DINO-Foresight [1] explores forecasting future features extracted from a pretrained foundation model instead of forecasting future frames. Once these features are available, any predictor can be attached on top to perform tasks such as segmentation, depth estimation, and potentially control without ever generating a single pixel. Sounds cool? Let’s see how this works in practice.

The architecture

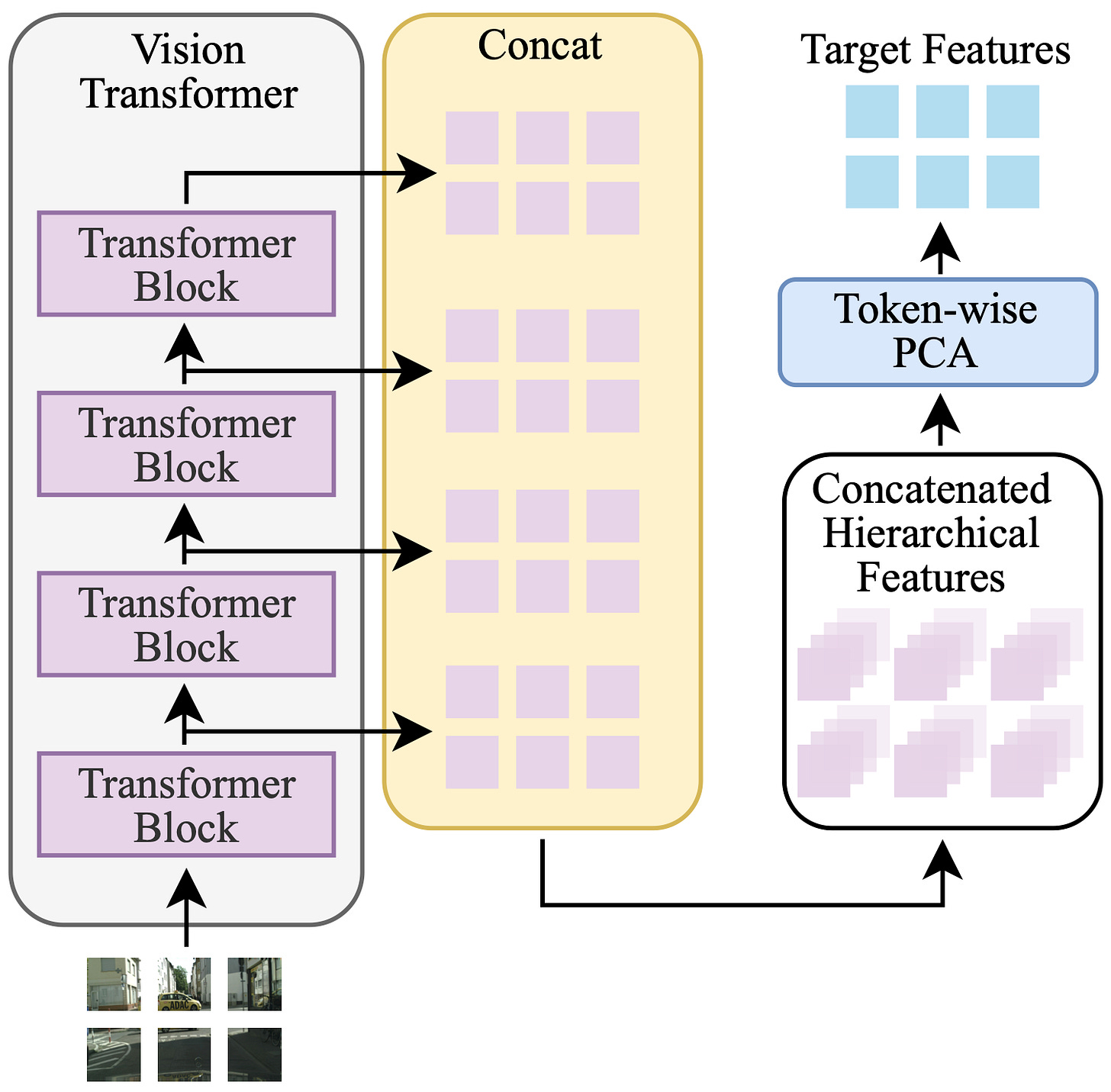

The key idea here is moving from pixels to features. Each frame of a video is first passed through DINOv2 with registers [2] in its ViT-B/14 variant, capturing spatial and semantic information. The resulting features have lower resolution due to patching (for example, a 224×448 image becomes a 16×32 grid of tokens), making them much more manageable.

Traditionally, we would take features from the last layer as image embeddings. However, the paper builds a stronger representation by stacking multiple layers from the ViT encoder. Each layer produces a feature map of shape H×W×D, constant across layers since it is a transformer. By taking all 12 layers of ViT-Base and stacking them token-wise, we obtain a representation of shape H×W×(12D), with over 9000 channels per spatial location.

But since these channels come from consecutive transformer layers, many of the dimensions are strongly correlated. Therefore, we don’t want this to be our target. Instead, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) projects this large feature vector into a space slightly larger than the regular embedding dimension. This has been shown experimentally to capture more information than using only the final embedding.

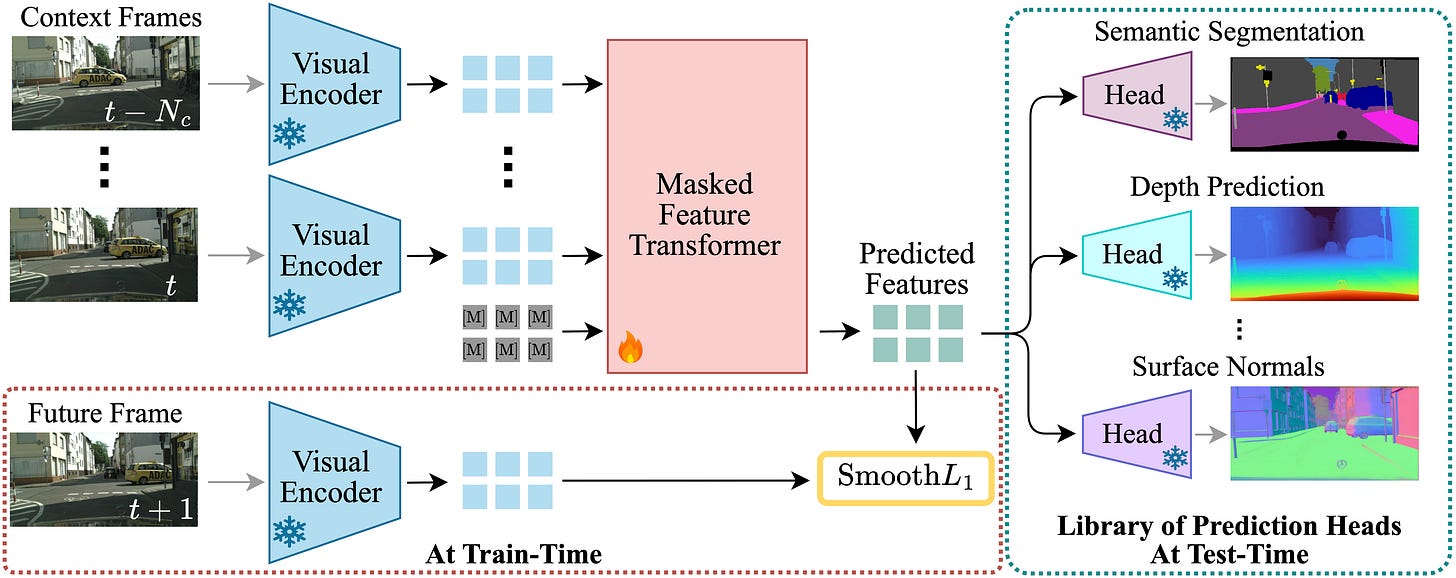

Now, given some frames as context and future frames as target (4 and 1, respectively), we can think of training a PCA-compressed feature predictor. A transformer is used for this part, following a masked prediction setup. In simple words, the compressed features of the context frames are passed to the model, while the features for the future frames are replaced with a learnable [MASK] token. This turns future forecasting into a self-supervised regression problem, without the need for any manual labels or extra supervision.

During inference, these [MASK] tokens are appended after the context frames, making sure there is no training-inference mismatch. Each token also receives a position embedding to retain both temporal and spatial information across the sequence. This way, the model has all the tools to learn scene dynamics.

To train, a SmoothL1 loss is applied between the predicted features and the ground truth ones at the masked locations. SmoothL1 basically behaves like L2 near zero and like L1 for larger errors, which helps training stability.

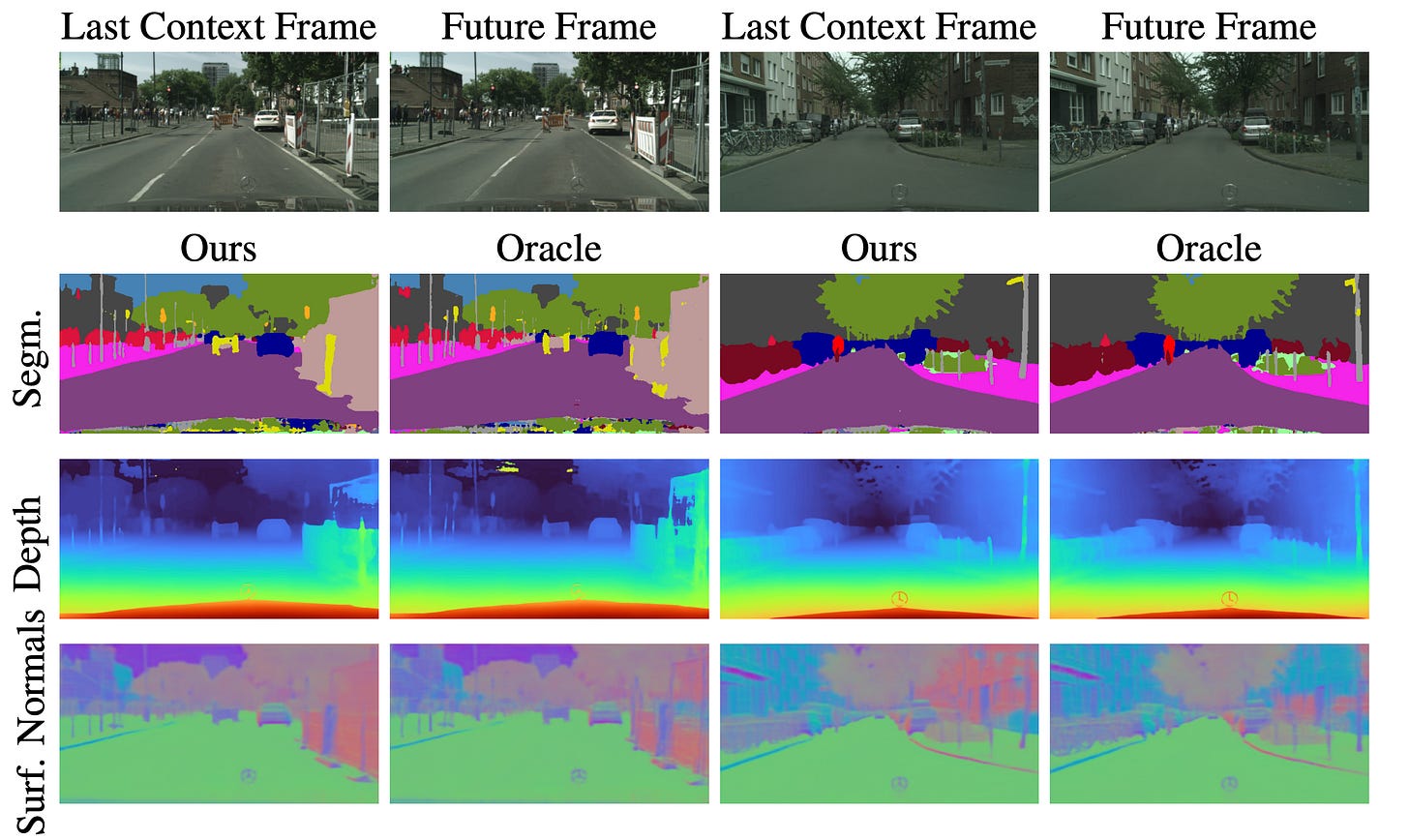

Once this forecasting transformer is trained, the rest of the pipeline becomes very flexible. The predicted features live in the same PCA space as the real DINO features, which means any downstream head that works on DINO features can also work on the forecasted ones! The authors experiment with classic dense prediction tasks like semantic segmentation, depth prediction, and surface normals estimation.

Training and inference tricks

Here are a couple of cool tricks you might want to consider for your research or production experiments. Those are equally important these days!

Efficient attention patterns. Because the sequence is very long, training with full attention would be too expensive. Inspired by the design of recent video transformers, the attention is split into temporal and spatial components. This keeps the computation efficient while still capturing the important structure in the data. Temporal attention is applied across tokens with the same spatial position in different frames, whereas spatial attention operates within individual frames. Thus, each transformer block consists of a temporal Multi-Head Self-Attention (MSA) layer, a spatial MSA layer, and the classic feedforward MLP layer.

Two-phase training with resolution adaptation. Using high-resolution features is key for pixel-wise scene understanding tasks where low-resolution features would otherwise struggle to capture small objects or fine spatial structures. Inspired by the DINO training schedule, the authors also employ a two-phase strategy. First, the model is trained on low-resolution frames (224 × 448) for several epochs, focusing on learning broad feature forecasting. Then, the model is fine-tuned on high-resolution frames (448×896) for a small number of epochs, adapting the position embeddings through interpolation.

Temporal extrapolation. The model is trained on consecutive frames, but nothing prevents us from pushing this further when doing inference. In particular, we can auto-regressively feed the model its own predictions and use those as the new context to look a couple of steps further ahead. Similarly, increasing the stride between input frames could also be a possibility, letting the transformer predict longer-term dynamics.

Conclusions

DINO-Foresight demonstrates that we don’t really need to generate exact RGB values when the goal is to forecast dense prediction values on video. By shifting the problem into feature space, which is what most perception models operate on anyway, we can focus on the information that actually matters rather than spending computation on textures, colors, or other pixel-level details.

The result is a model that is efficient and task-agnostic, useful for many domains such as autonomous vehicles, robot navigation, and video reasoning. And as foundation models get better, this approach of using frozen features with a lightweight forecasting module will only become more appealing.

This paper will be presented at NeurIPS in San Diego next week, so you might wanna check it out in person if you are there. Thanks for reading, and see you in the next one!

The idea of moving from pixel forecsting to feature forecasting is really clever, especially for tasks like autonomus driving where you care about segmentation or depth but not necessarily RGB details. I wonder how the temporal extrapolation holds up in practice when scenes have sudden changes or occlusions. Does the model start to degrade fast or does it stay surprisingly robust?