46. Concerto

Joint 2D-3D self-supervised learning on point clouds

Introduction

Foundation models for 2D images are well established at this point, with architectures like DINO and CLIP learning powerful features from massive image datasets. Oftentimes, these models are used as frozen backbones, requiring only a linear probe or lightweight fine-tuning to adapt to downstream tasks.

But when it comes to 3D, we unfortunately didn’t have this luxury. While there is plenty of point cloud data from autonomous vehicles and robots (and we can also generate more from videos and/or depth estimation), developing foundation models remains challenging as 3D data is sparse and lacks the rich semantic texture of images.

Approaches like Sonata [2], described below, have pioneered self-supervised learning in 3D. However, they also made it clear that learning robust 3D representations in isolation is challenging. So, a natural question arises: can we train a model on both 2D and 3D data simultaneously? At the end of the day, an image is effectively just a projection of the 3D world onto a camera, so it makes sense to learn from both!

Building on this insight, Concerto [1] proposes a unified framework for joint 2D-3D self-supervised learning that aims to bridge 3D understanding with the robust feature extraction capabilities of pretrained 2D foundation models. If this sounds exciting, you are in the right place!

Background: PTv3 and Sonata

Two essential components are baked into Concerto, and we should introduce them before examining the main framework.

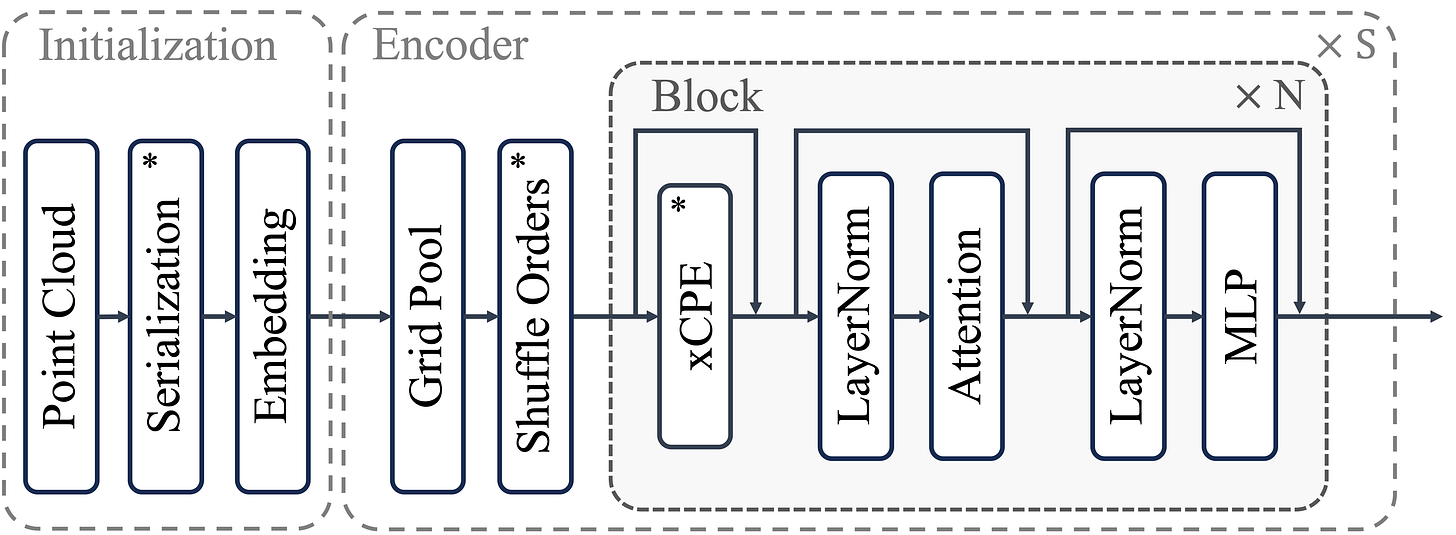

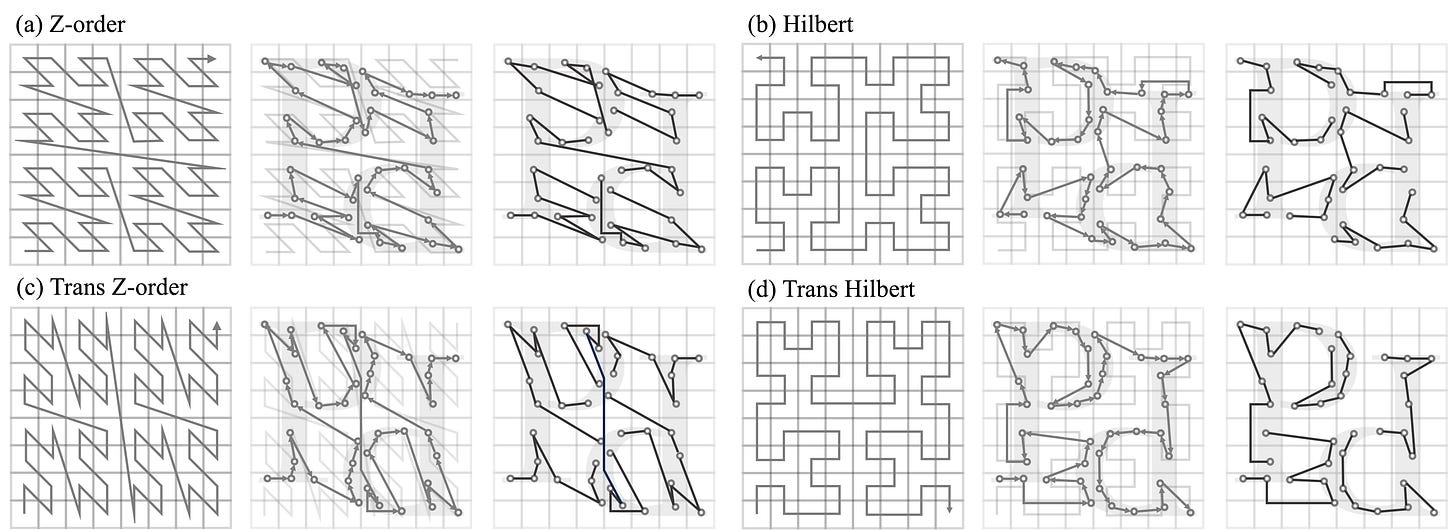

The first is Point Transformer V3 (PTv3), the latest iteration of a transformer-based backbone for processing of point clouds. To handle their unstructured nature, PTv3 introduces point serialization via space-filling curves. Simply put, we traverse every point in 3D according to a set of predefined logic, effectively mapping the data into a manageable 1D sequence while preserving spatial proximity to a significant extent. Its four serialization patterns are shown below.

Overview of the serialization process. Left: four space-filling curve patterns used for serialization. Middle: resulting 1D point sequence sorted via the space-filling curve. Right: serialized points grouped into patches for local attention. From [3]. This allows the model to apply standard efficient attention mechanisms after local grouping, scaling to large scenes efficiently without any custom design. While the original architecture of PTv3 consists of a four-stage encoder and decoder (similar to a U-Net), only the initialization + encoder part is kept here.

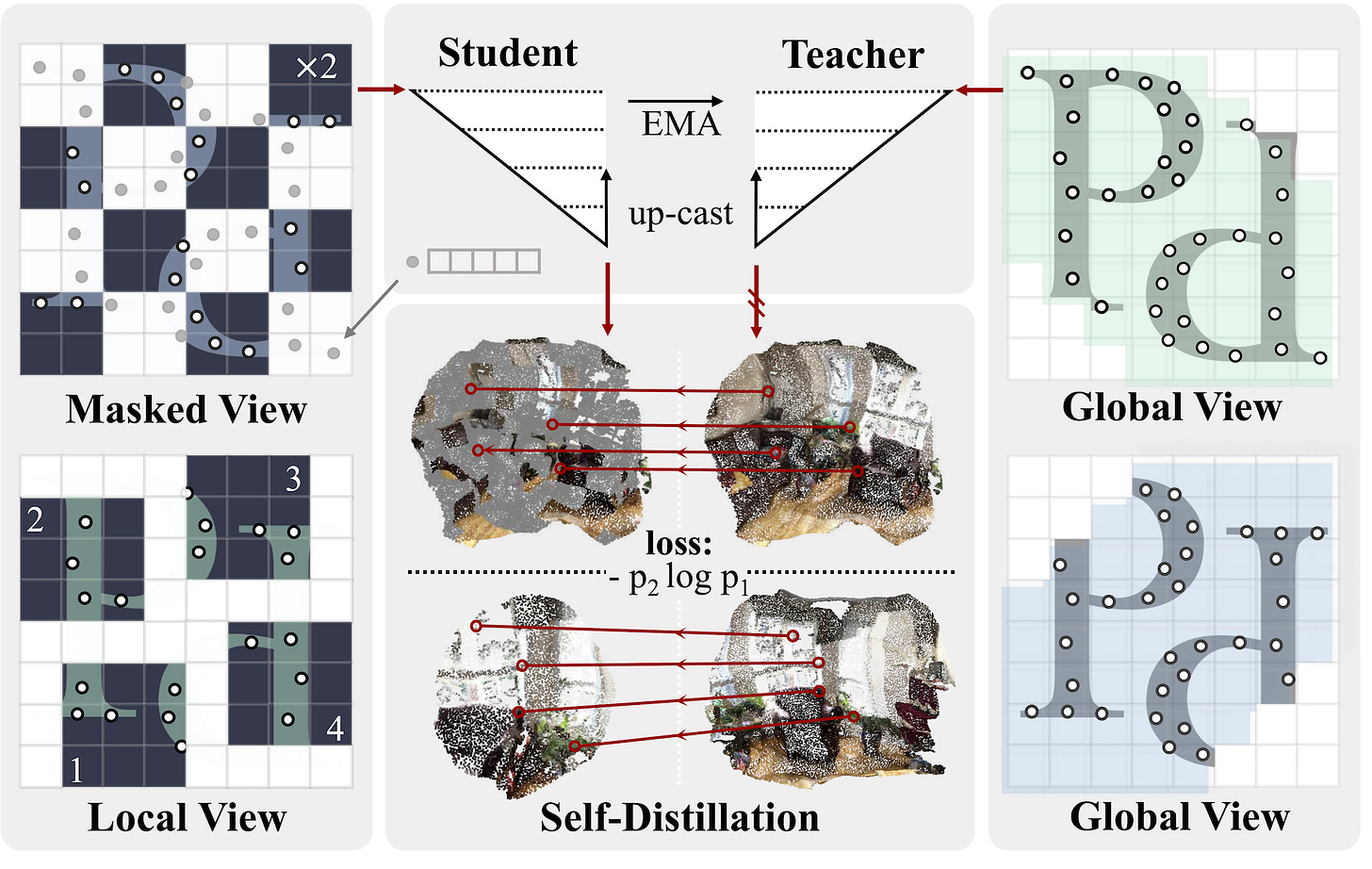

The second is Sonata, a DINO-like self-supervised learning framework built on top of PTv3. In practice, it takes multiple views of the same 3D scene, applies random spatial (crop, rotate, distort) and photometric (jitter) augmentations, then trains by matching the embeddings of points that are the same. However, since geometry alone encodes substantial information (e.g., via surface normals), masking is used to prevent the model from taking easy shortcuts. Similar to DINO, local and masked views are passed to the student, while the teacher processes global views.

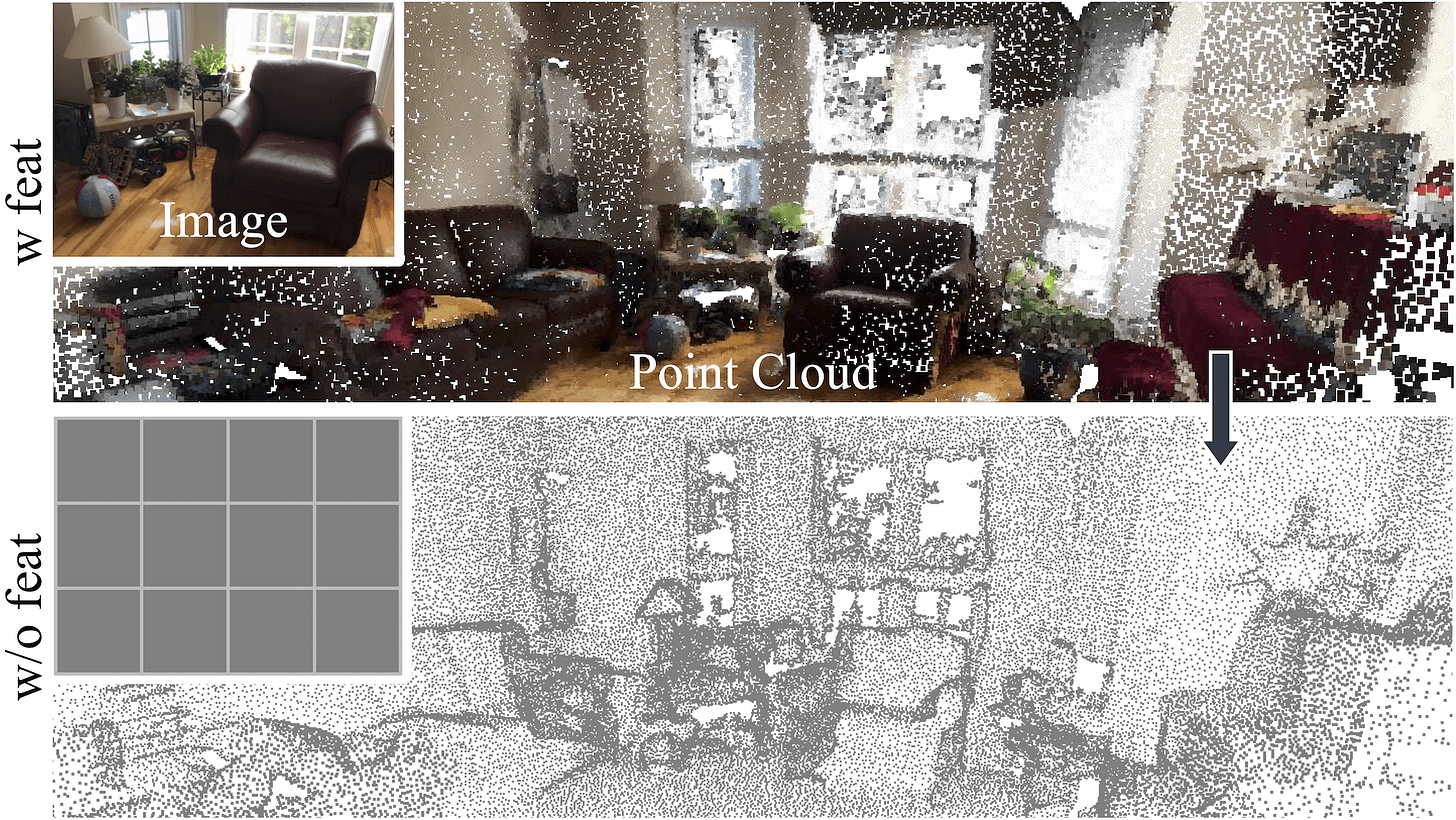

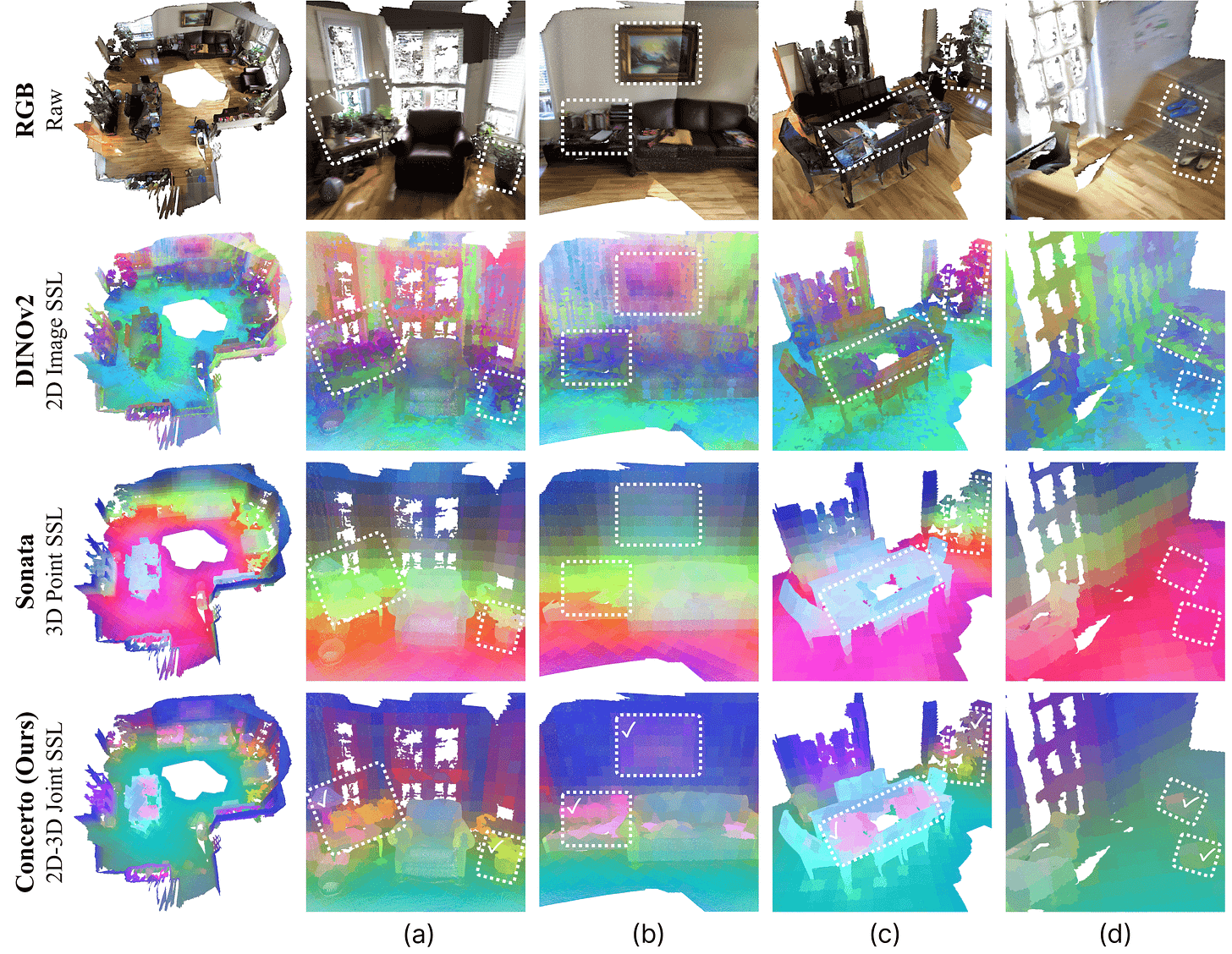

The model generates local, global, and masked views with spatial and photometric augmentations. A student network processes local and masked views, while a teacher processes global views. Features are distilled by matching point features across views. From [2]. Since the framework does not require labels, by training on 140k scene-level point clouds, both real and synthetic, Sonata establishes itself as a powerful pretrained encoder for any downstream 3D scene task. However, despite these capabilities, the model still tends to over-rely on low-level geometric cues rather than top semantics, which is a natural limitation of working solely with sparse point data. The difference between 2D and 3D is clear when looking at this image.

DINOv2 enters the scene

The simplest baseline in a 3D task is often just to borrow what works in 2D. Since we typically know the camera pose and depth, we can take a pretrained image encoder, extract features from multiple corresponding frames, and lift them onto the 3D points via unprojection. And because image encoders like DINOv2 have seen hundreds of millions of images, they bring massive semantic knowledge into the 3D domain for free. For example, they clearly outline objects and cluster similar semantic areas.

Most importantly, Sonata features and unprojected DINOv2 ones are complementary. In fact, in the Sonata paper, the authors already show that simply concatenating their feature vectors achieves significantly better results than any single data modality alone (+3.9% and +7.7%, respectively). This observation is the idea for Concerto: if these two signals work well together but are so different, can we distill them into a single, unified model?

Architecture of Concerto

The core idea here is that 2D and 3D data describe the same physical reality. An image captures a perspective, while a point cloud captures the structure. Concerto encourages the model to align these two views.

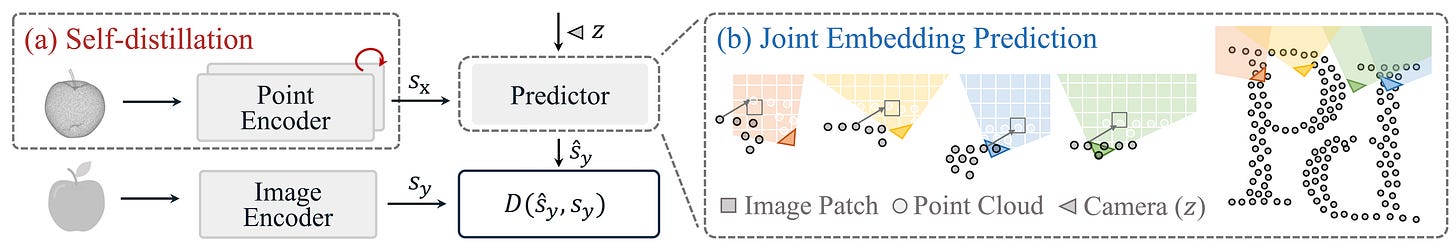

The architecture uses a unified transformer, the same PTv3 as Sonata. However, the training recipe is upgraded to handle multimodal signals. The model is trained to satisfy two objectives simultaneously:

Intra-modal self-distillation (the geometric teacher). Just like in Sonata, the teacher model processes the point cloud, and the student must predict the representations from masked or augmented views. This ensures the model maintains a strong, independent 3D-native understanding of structure and scale.

Cross-modal alignment (the semantic teacher). This is the introduced novelty, following LeCun’s Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture (JEPA), which advocates learning by predicting latent representations across modalities. In this setup, the student model (processing the 3D point cloud) employs a predictor head to approximate the representations produced by the frozen 2D teacher. The alignment mechanism is explicit: for each image patch, the model computes the mean of the features of the points that project into it, and maximizes cosine similarity with the image counterpart, effectively forcing the 3D features to align with the semantic concepts in 2D.

By optimizing these two losses together, the 3D model learns to augment and regularize the geometric shapes with rich and far more general semantic concepts learned from images. The effect is striking at both the object and conceptual levels. For instance, in views (b) and (d), Concerto produces very uniform features across semantic regions like the wall, floor, and window. In contrast, Sonata tends to overfit to the raw geometry. This is clearly visible when looking horizontally at a fixed height.

The regularization given by meaningful DINOv2 features forces the model to smooth out these geometric artifacts and learn a representation that respects 3D object boundaries and function rather than varying across coordinates.

This architectural synergy is also clearly reflected in the metrics, where Concerto consistently outperforms its single-modality counterparts by a significant margin, surpassing both standalone SOTA 3D and 2D self-supervised models by 4.8% and 14.2%, respectively. And you can only guess what happens when swapping this old DINOv2 out for an even superior, multi-view consistent DINOv3!

Conclusions

Concerto shows that it is possible to combine the geometric precision of 3D-native models and the general semantic power of 2D foundation models into a single 3D point cloud encoder. In particular, by distilling the massive knowledge of large-scale image encoders into a 3D backbone, we can create spatial representations that get the best of both worlds.

This work suggests that the future of 3D is less about better point cloud architectures and more about repurposing the multimodal signals available. The Concerto encoder is also very exciting as it paves the way for future simplified 3D annotation (aka, a Segment Anything in 3D!) and open-vocabulary spatial understanding, bringing us closer to a universal foundation model for the physical world. Thanks for reading, and see you in the next one!

References

[1] Concerto: Joint 2D-3D Self-Supervised Learning Emerges Spatial Representations

[2] Sonata: Self-Supervised Learning of Reliable Point Representations